May 1st through 5th.

Driving down a lonely, gravel road in Nevada, I was excited, nervous, optimistic. Helen, my wife, was dropping me off at a “faint Jeep track” where I would start my Great Basin Trail (GBT) hike. She needed to get down to Las Vegas, return the rental car and fly home. We kissed, hugged and said goodbye for the next two months and she headed to the freeway. I headed into the sagebrush.

Storm clouds loomed in from the west, but they looked mild and I hoped they would miss me. Eastern Nevada seems like a mighty creature reached down and pulled a rake through from south to north. Mountain ranges go along in neat rows and hot dry valleys separate them. I was happy for this valley to receive rain, but I wanted no part of it.

As I gained elevation, I left the comfort of just following an old jeep track. As I started to follow geographic features, the flora changed from sagebrush to sparse juniper and pine. The storm briefly caught up to me and gifted me with some light rain and even a few snowflakes.

I arrived at my first water source and it was glorious. Indian Spring is a developed spring flowing with cold clear water. It was the last reliable source for several miles.

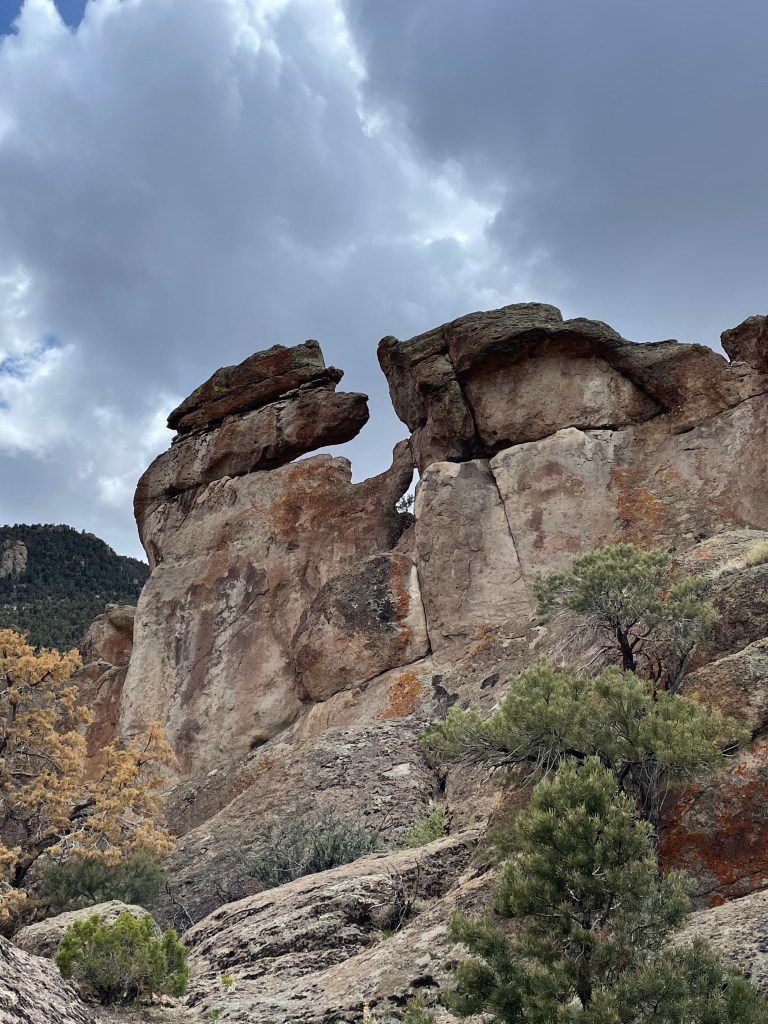

Leaving the spring, the route became very difficult. Scrambling up a rock formation, I tripped and extended my hands to cushion the fall. My phone, with detailed GPS information, bore the brunt and part of the glass cracked.

Next I entered a very steep area where I was to follow game or elk or horse trails. There are three problems with this. First, animals are great pathfinders, but will vary their routes based on changes (tree falls, presence of predators, etc.). Second, in the early season the animals are lower enjoying the spring grass and giving birth. Third, I am 6’4” while deer are three feet from the ground at the shoulder. Thus, even if I get on a horse trail, my shoulders and face are pushing through branches that they miss.

I was making less than one mile per hour. The terrain was getting rougher with rocky cliffs. I fell again. This time slamming down on one of my carbon fiber trekking poles, snapping it. Towards dark, I did an assessment: almost all my water was gone, I was not going to reach my planned campsite, and somewhere along the way, my umbrella had been removed by a branch. Oh, and because I had been using my phone’s GPS mapping all day, my battery was nearing the single digits.

So I pushed toward the nearest possible water source. As it got darker, I made my way up a dried stream bed. By the markings in the stream bed, other creatures had done this already. As the canyon narrowed, I finally found a slit in a rock containing a deep pool. Pushing aside the top layer of green growth i filled my filtering water bottle. I was glad that green is one of my favorite colors because in the fading light I could see a green hue even after filtering. “Wilderness wheatgrass”

The next day was more route finding among trees and shrubs, ending with a nice dirt road walk. I started to appreciate the silence and the smells. Smells from the plants, to be clear. Juniper, sagebrush, mountain mahogany, pine. If there was no wind, it was vast, pure silence occasionally pierced by a jet far overhead.

The third day was brutal. Mostly pushing through mountain mahogany and then, later, weaving through manzanita. I’m not a botanist, so excuse my oversimplified descriptions. Mountain mahogany is a tall shrub with a unique smell, interesting bark, and branches designed to shred clothing, slash arms, and remove hats from passers by. Manzanita is a low growing shrub with waxy green leaves, charming little pink flowers, and numerous thick sharp branches designed to cut shins, grab feet, and hide the ground. I ended up on a high windy ridge dotted with manzanita as night fell. I tucked in next to a burly manzanita that blocked the wind. I cowboy camped under a vibrant starry sky watching satellites ceaselessly perform their orbits.

My fourth day witnessed huge elevation gains. It began with an unexpected surprise. Someone had cleared a six foot wide swath through the thick shrubbery and marked it with cairns. Was it a hunter? And old sheep herders route? A misguided, overzealous Scout troop earning their shrubbery badge? Regardless, I was happy and smiling.

The smile wore off as I looked up and ahead. In the distance, on a barren mountain at 9,200’, stood the radio towers I would climb to pass. The path was dirt road and it was sunny and in the 50s. I knew I had to continue working on my uphill and downhill muscles for the mountains later in my trip.

The views from the top were vast and great. I could look back and see where I started. The other direction I could see the tiny reflections of Pioche, my next resupply town. I sipped some of my dwindling water and began a knee-crunching descent. It was sunny, not windy and bereft of interesting things to look at, so I changed into shorts, fired up an audiobook, and set my own personal cruise control. There was, however, an intriguing geological feature. It was a large black, square lava tube that jutted sharply out of the forest floor. The top was almost flat with a miniature forest growing on top.

Having never seen a car all day, I walked in to my last water source, Page Creek Spring, where I would spend my last night before town. It was warm water with many green plant forms. Fortunately as I made my way up one side to find the source, I found a tiny spring releasing clear cold water. It was perfect.

There was an abandoned structure on site. An amalgam of stone, wood, and corrugated steel, I tried to figure out it’s former role. Home, loafing shed, who knows. I again cowboy camped on public land. However this night it was not windy. Very quiet and still except for the one round of coyote howls to each other across the valley .

My final day was a warm 20 mile road walk in to town. Desolate country. Besides one band of wild horses, it was just me, horned toads and lizards and an occasional antelope in the distance. I saw my first car and person since Sunday as I neared Pioche. It is pronounced pee oh shh. Grabbed a sandwich and water, checked into my motel and started my “town” routine.

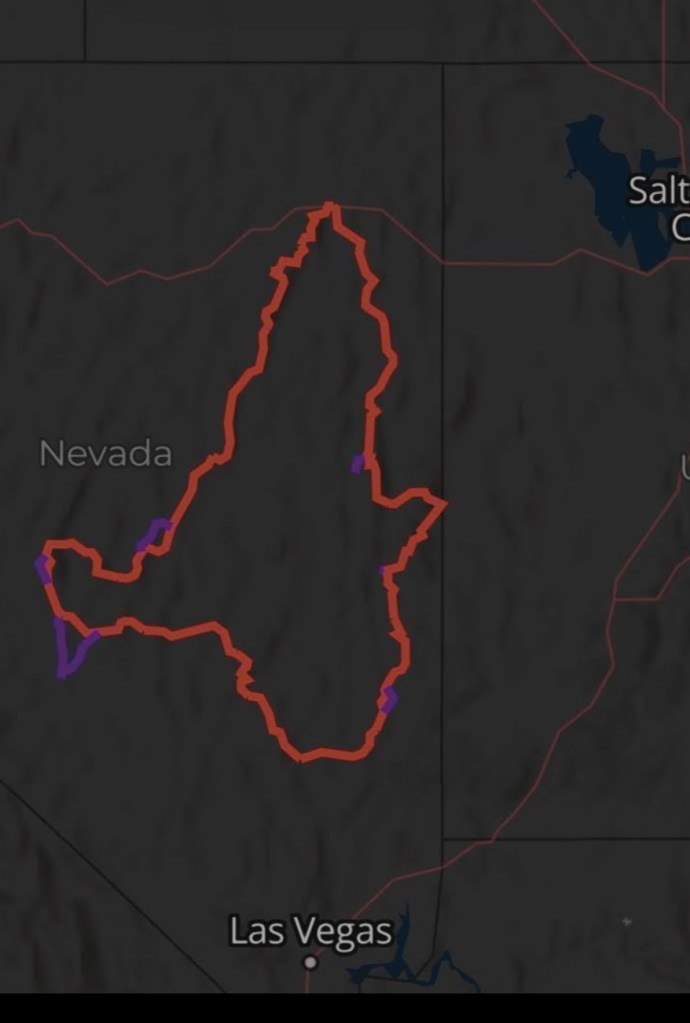

In summary, it took me one day longer to travel 85 miles. This trail is tough. I have to get better at not using my phone GPS map every five minutes. This trip is going to be far less following a trail and much more forging a route. It is big, windy, lonely and I like it.